Let’s first reflect on a few things…

The clips that I don’t own come from here, here and here. Also as a disclaimer, I am not affiliated with Google Glasses nor do I own any (RIP).

Setting the scene

Perth has big plans for it’s CBD. As part of a so-called construction boom, there are some new skyscrapers in the works – including what would be the tallest of the bunch! The $100 million, 62-storey apartment complex at almost 250 metres high will undoubtedly be a tall order. But will this help us to reach new metropolitan heights or will it just make it harder to keep our feet on the ground? There are many factors that make it difficult to determine whether or not building upwards is a good thing in itself – regarding the social, economic and ecological implications. However, for the sake of this argument let’s assume that construction of these beanpole buildings is going to go ahead. This blog aims to develop a business case for how these can be built in better ways, given that they are going to be built at all.

The base case

Skyscrapers are generally not considered eco-friendly – Dr. Ken Yeang, an expert on ‘ecoskyscrapers‘ says that tall structures usually consume over a third more energy and material resources than other types of buildings – during construction, operation and demolition. From an engineering standpoint, one of the most obvious concerns is ensuring that the building remains structurally sound under any possible conditions. At higher altitudes, the wind has more attitude produces larger bending moments on the building’s structure, hence expert engineering is required to ensure sufficient reinforcement. Add to this the complexity of pushing objects against the force of gravity (aka lifting) – cranes are needed to lift building materials, elevators are used to lift humans, and water needs to pumped up to the highest floors.

Time-lapse of a skyscraper build. Image: EarthCam

Some of these issues are unavoidable when building a high-rise. It’s not easy to make something that tall. But when it comes to people achieving the seemingly impossible – they usually can, within reason. Technology advancements would allow us to build almost anything conceivable, if it wasn’t for certain limiting factors. In financial terms, the limit is represented by the cost. However, as discussed in my blog post on ecological economics, the financial cost is really just the way we quantify its perceived value. The real limits are due to the finite resources available on this planet. One of the big ones is energy, which is needed for practically everything. There’s a pretty significant world crisis revolving around this crazy stuff, and everyone is wondering what’s going to happen if we continue to consume resources without replacing them. It’s clear that we need to minimise excessive energy consumption.

There’s something else that needs to be pushed to the extremities of these towers – air. Specifically, air at highly regulated temperatures intended for optimal human comfort. Air conditioning is a huge part of modern building design. According to Professor Alan Short, an expert in Architecture from the University of Cambridge, buildings in western cities account for around half of all electricity usage, heavily contributing to carbon emissions. Short suggests that these numbers are so high partly due to poor design for air circulation and temperature regulation. The conventional design of large buildings has involved sealing them up and relying on powerful A/C systems to make them habitable.

Conventional tall buildings require enormous quantities of energy. It is grossly inefficient to build something that has no natural resilience to the climate, and to overcome these shortcomings with excessive electrically-powered air conditioning. The base case considering ‘conventional engineering’ is looking pretty stagnant and bleak…

Surely there’s another option?!

You better believe it! Maybe we can compare ‘conventional engineering’ to its fresh-faced younger cousin: ‘ecological engineering’. Imagine if it was possible to design a building that provided all the necessary services and similar levels of comfort, without resorting to blasting A/C all day everyday? What if a building could regulate its own temperature, by integrating with the environment rather then being sealed off from it? The good news is we know it is possible – because it’s been done before. Long before – hundreds of years ago actually.

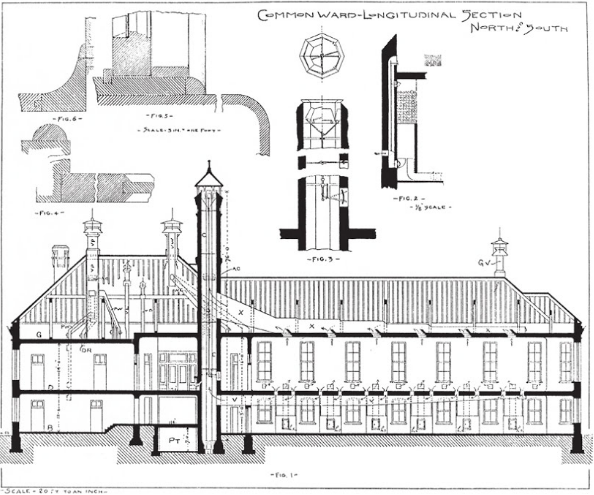

19th Century buildings such as hospitals, theatres and schools had dedicated a large portion of their design to improving ventilation. A driving motivation behind this were the recent outbreaks of diseases such as cholera.

Inpatient ward at John Hopkins Hospital. Images: Stephen Verdeber

One of the geniuses behind these revolutionary building designs was John Shaw Billings. The images above show the inpatient ward of the John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore (from Stephen Verdeber’s book Innovations in Hospital Architecture). Aspects of this design included small vents in between the beds which allowed for fresh air intake, and a basement level which acted as a fresh air reservoir.

This concept of natural ventilation relates to the issue of dependence upon technology. Modern hospitals now have computer-controlled systems to regulate the air conditions. I am not suggesting replacing those, but rather finding an optimal hybrid system which utilises natural and artificial methods. My point is that we could reduce power usage by using as much natural, passive technology as possible, and using the artificial, carbon-heavy technology as a support or back-up. This same idea can be applied to air-conditioner usage in skyscrapers.

Because technology is capable of reducing the consequences of risks, we tend to care less about the likelihood of the risk. I find it interesting that you can apply this idea to so many things. Lack of hygiene could result in infections spreading, but is it really that important when antibiotics are readily available? Making mistakes while writing a paper was once costly, and you may have had to start again. But modern computers allow you to undo so easily, so we care less about sloppiness. You might make a blunder while playing sport, but hey you can always blame the referee! Oh, and so what if this library can’t cope with the climactic variation? A few more power generators will sort that out.

No-one needs to know that I suck at typing! Image: KyTyper

In all these cases, I think we rely too heavily on the back-up plan and in fact expect it to eventuate. Back-up plans should be treated as a last resort, and we should take responsibility to prevent these issues from occurring wherever possible. I think this is a key to developing smarter designs as an engineer, and in doing so fewer resources will be consumed. This is why we shouldn’t design dumber, just because smarter designs are less crucial thanks to technology.

This is everybody’s business

There are many benefits of designing buildings to integrate better with the surrounding ecology, and questioning the conventional use of technologies. Let’s go through a few of them. This link also lists some advantages of using eco-friendly construction companies.

Keeping the birds and the bees (and the trees) happy

The environmental benefits have to be the most obvious. Of course green buildings that use less electricity also provide less pollution to the atmosphere. Also by increasing the efficiency of building technologies, fewer natural resources would be consumed. Adding green roofs or walls would also complement natural ventilation to regulate temperatures and reduce the amount of cooling required. These could also become part of a green corridor that encourages biodiversity in urban areas. Another important factor is how these buildings deal with water – by collecting rain, reducing waste and providing efficient ways to filter and recycle water, this valuable resource could be preserved.

Money money money

The people who carry briefcases and enjoy nodding their heads while sitting in long boardrooms love this one. The reality is that in this economics driven world, financial factors are really gonna make or break the case. People who oppose these projects (those that make $$$ from the alternative) will argue that ecoskyscrapers will be too expensive to implement:

“Yes, yes, we get it, you like green things but get your head out of the clouds ya dumb hippies” – Mr. Mining Magnate 2017

Don’t worry about that guy though. The fortunate flip side to this coin is that ecological design actually improves the economy. For starters, the ecology contains an incredible amount of intrinsic value that is difficult to observe or quantify – see Growthless Value if you haven’t already. One thing about building smarter – and greener – is that capital costs can often be offset be lower operation and maintenance costs. This can be achieved through efficient use of resources such as water and energy.

A study by GSA found that green buildings were performing with 45% less energy consumption, 53% lower maintenance costs and 39% less water usage. These buildings also have lower vacancy rates in general, and a lower overall life cycle cost. In addition to this, the expansion of the green building industry will add to the job market.

It looks good and feels good too

Okay so I know appearances are subjective, but come on – surely you would agree that this looks a little more interesting than the steel and glass pillars that erupt from our cities?

Does green or grey suit me better? Image: Inhabitat

Green buildings have also been found to have a positive effect on human health (through the use of non-toxic materials), and improved occupant satisfaction. Isn’t the ultimate goal to improve quality of life? If the environmental and cost benefits weren’t enough, green buildings also provide psychological benefits! These smart designs provide natural lighting, high quality air and ergonomic features that improve living conditions.

It’s too late?!

There are so many tall buildings that are already built, we’re not just going to knock them down and start again are we? No. While there are many exciting new designs to push the limits of what’s possible and challenge preconceptions, it doesn’t mean we should ignore existing structures. Slowly but surely, their carbon footprints could be reduced through renovations. The skylines in the United States are not a pretty sight, when you’re looking at their electricity bills (urban buildings in the US were found to consume three times as much energy per floor area than in China). However, promising improvements are being made to some of the biggest office buildings the US, as shown in the infographic below.

It’s a good start guys! Image: Inhabitat

Wrapping it up

The case is clear that skyscrapers, and buildings in general should be designed to be more eco-friendly. By taking steps in the right direction, we should be able to design buildings that can improve our lifestyles, consume fewer natural resources and are more cost efficient. This can start with questioning the technology that is taken for granted, and investigating alternative ways to provide the same outcomes.

Thanks for letting me share these ideas with you, and please let me know what you think about it! ![]()